“I think there is no innocent landscape, that doesn’t exist.”

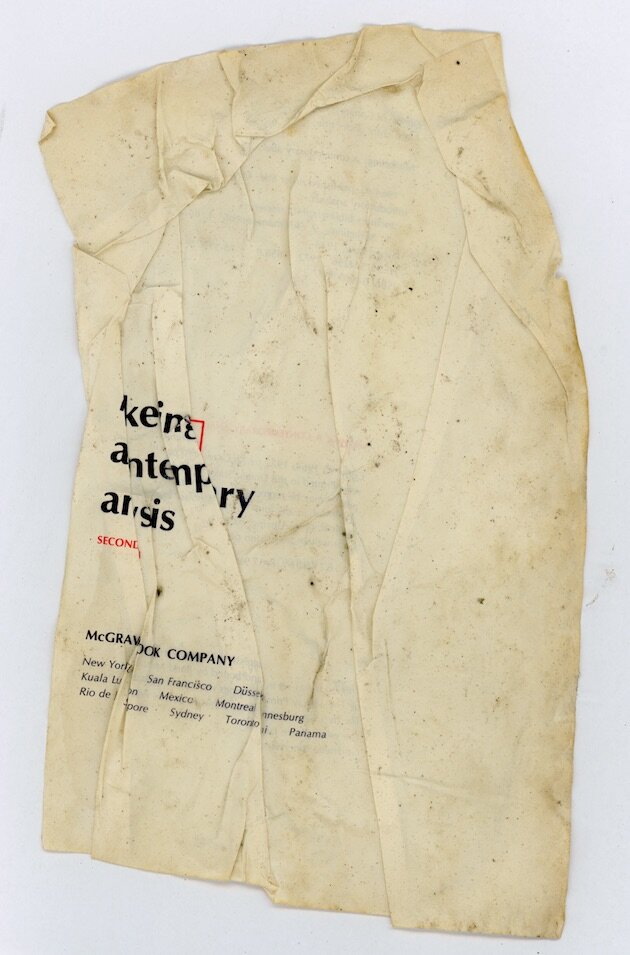

from Anselm Kiefer’s Relics of Violence

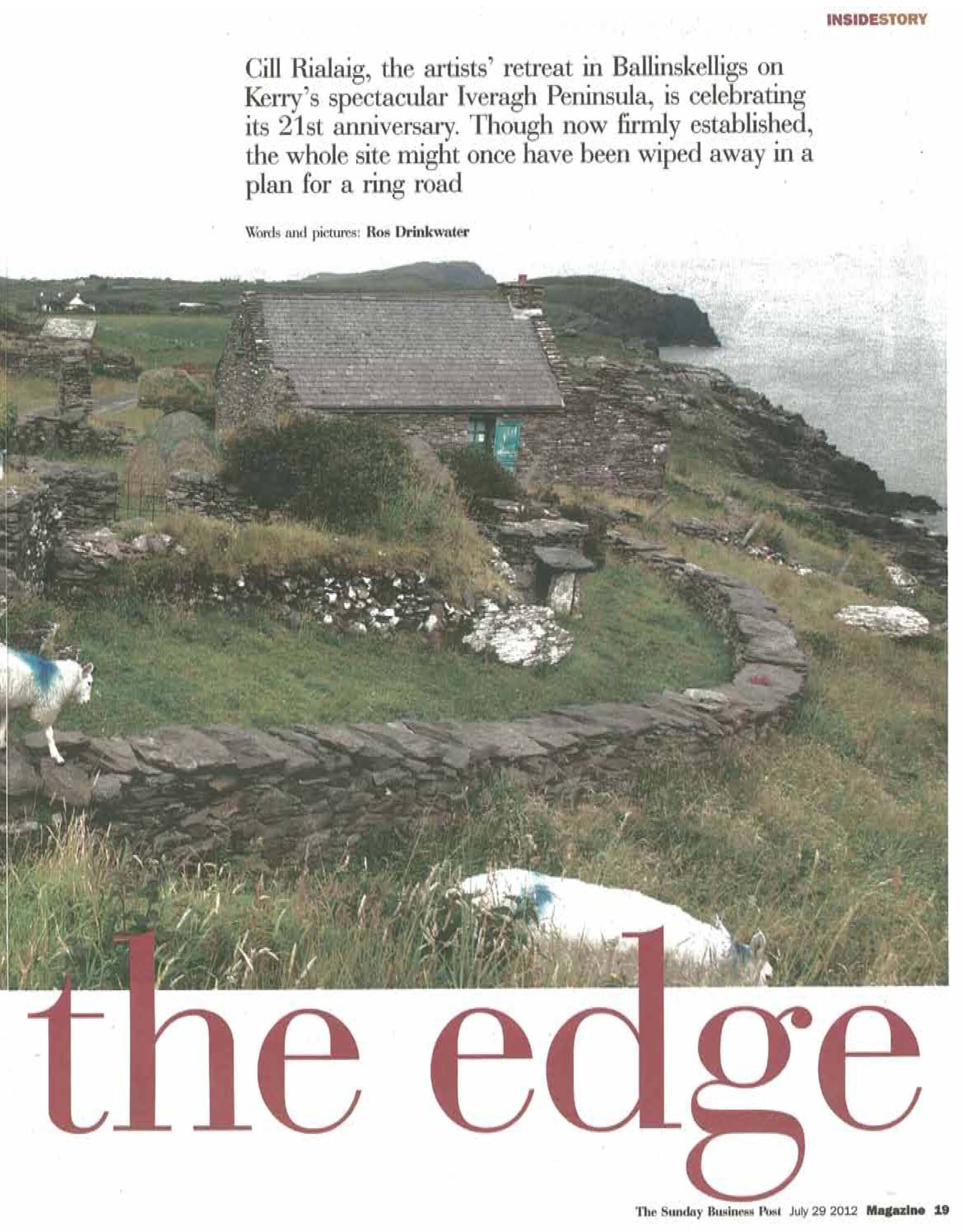

It’s already been two months since my return from Cill Rialaig, the artist retreat on the Iveragh Peninsula of County Kerry Ireland.

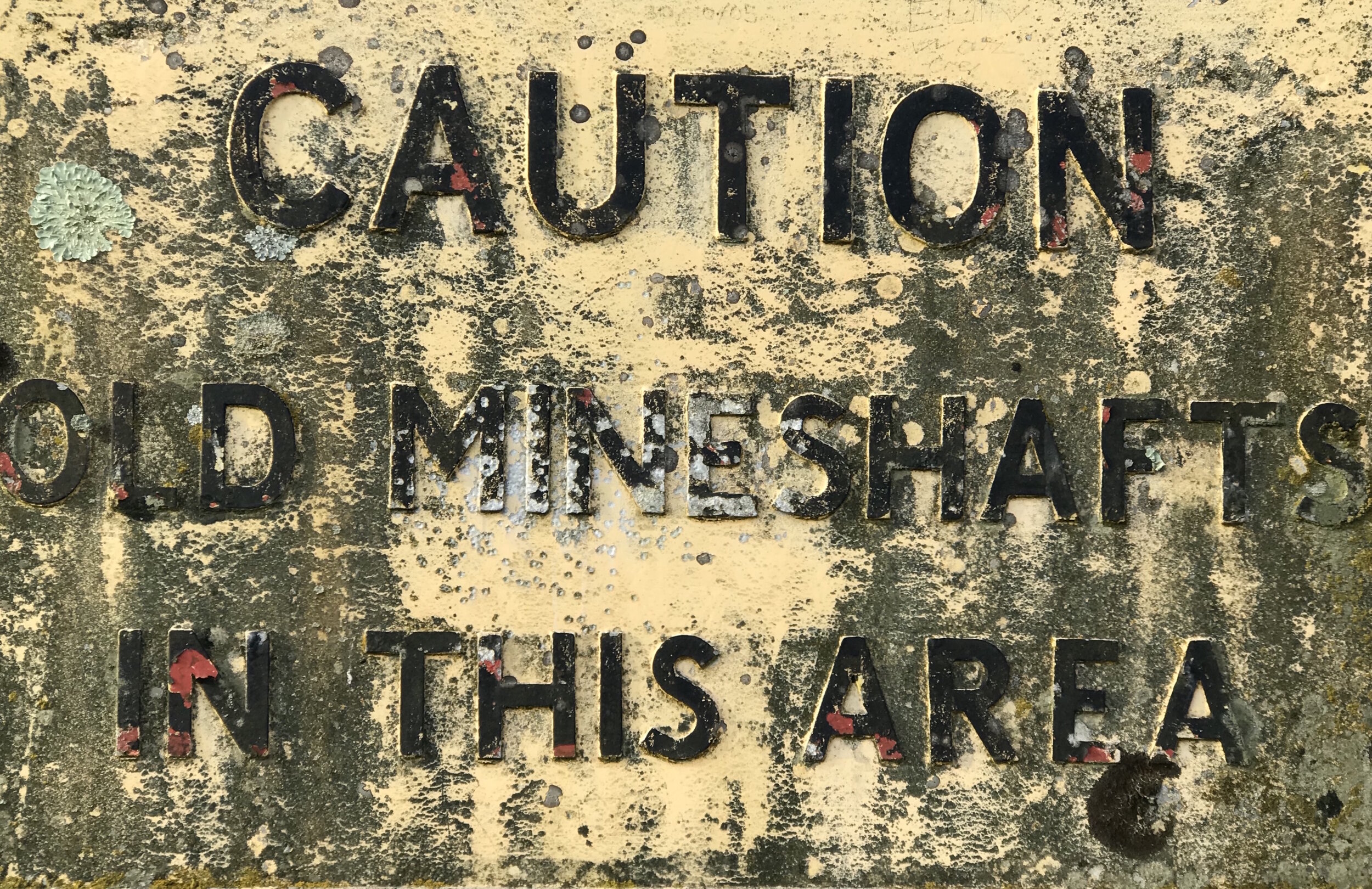

I went with artist, Catherine Richardson, to collaborate on Materiality, Re_Mined, a project we initiated in response to the call for action proposed in Extraction: Art on the Edge of the Abyss. The event slated for 2021, envisions worldwide participation and simultaneous showing of artists from around the world concerned about how “We are recklessly modifying every feature of the planet surfaces.”

We mostly worked independently guided by our own inspirations and impressions of the place except when we took field trips to mines and quarries in the area.

In those two months since my return, I have been working with some of the materials of Cill Rialaig that I discovered—as it was an unfamiliar source place with its own unique aura seeped in a difficult history with remains and remnants of a time.

My hope was to extract from what was there. What were those materials of this place that spoke to me?

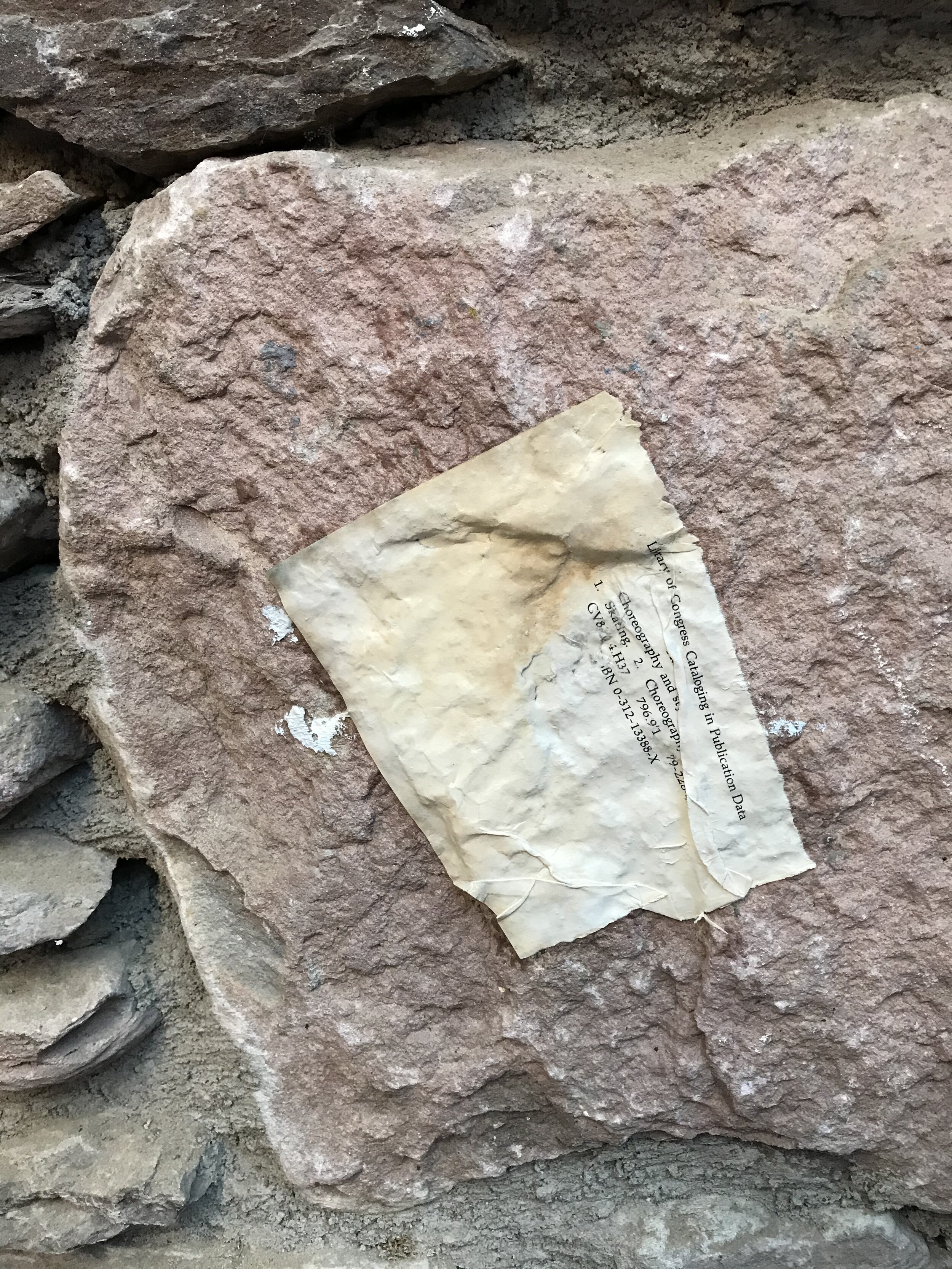

With a predilection toward stones and wind worn landscapes, I was at home surrounded by stones & rocks—the cottages, boundary walls, ruins, standing stones. A spectacularly beautiful place with memories in these stones—trace fossils that marked a past.

If the stones could talk, what would they say?

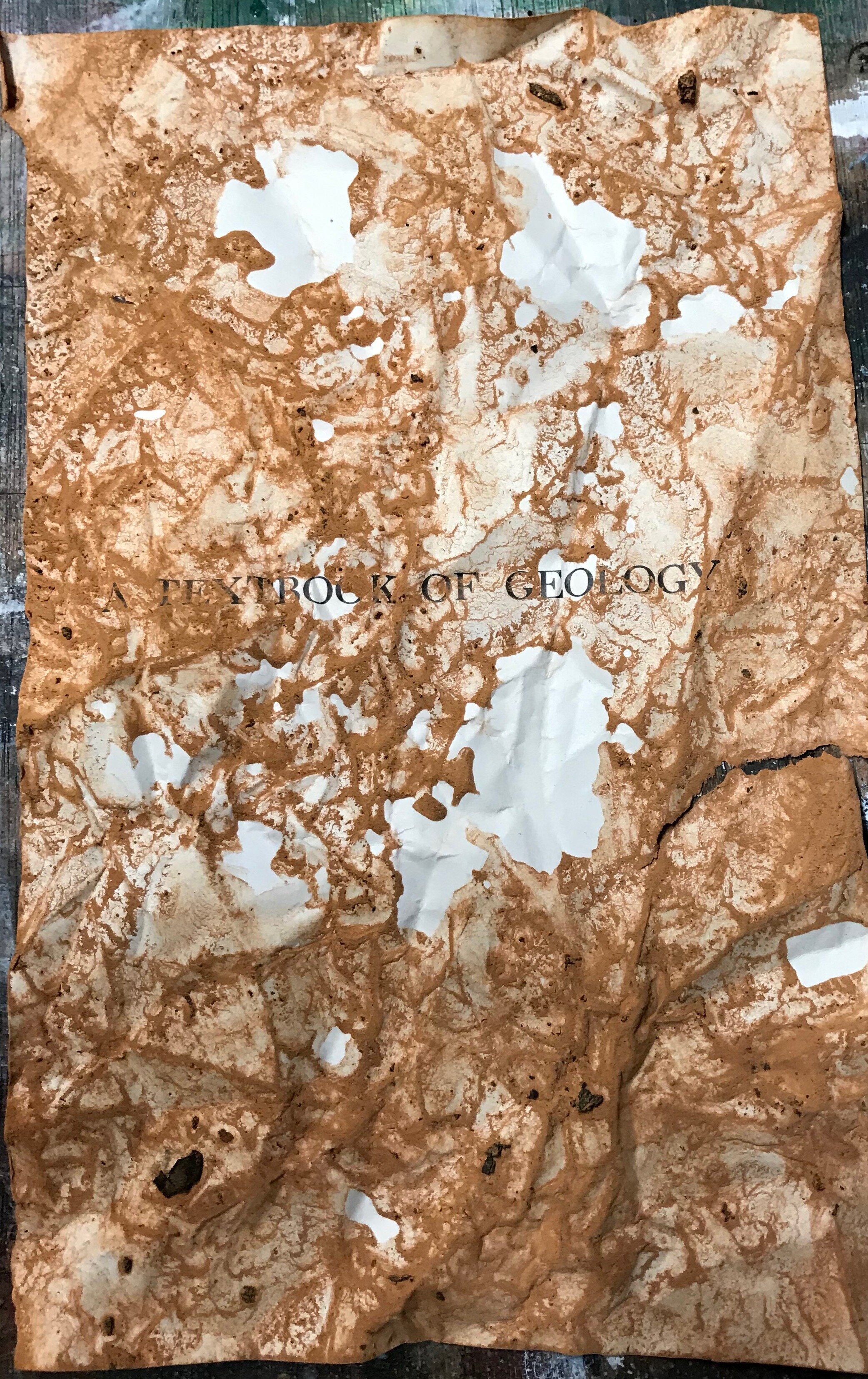

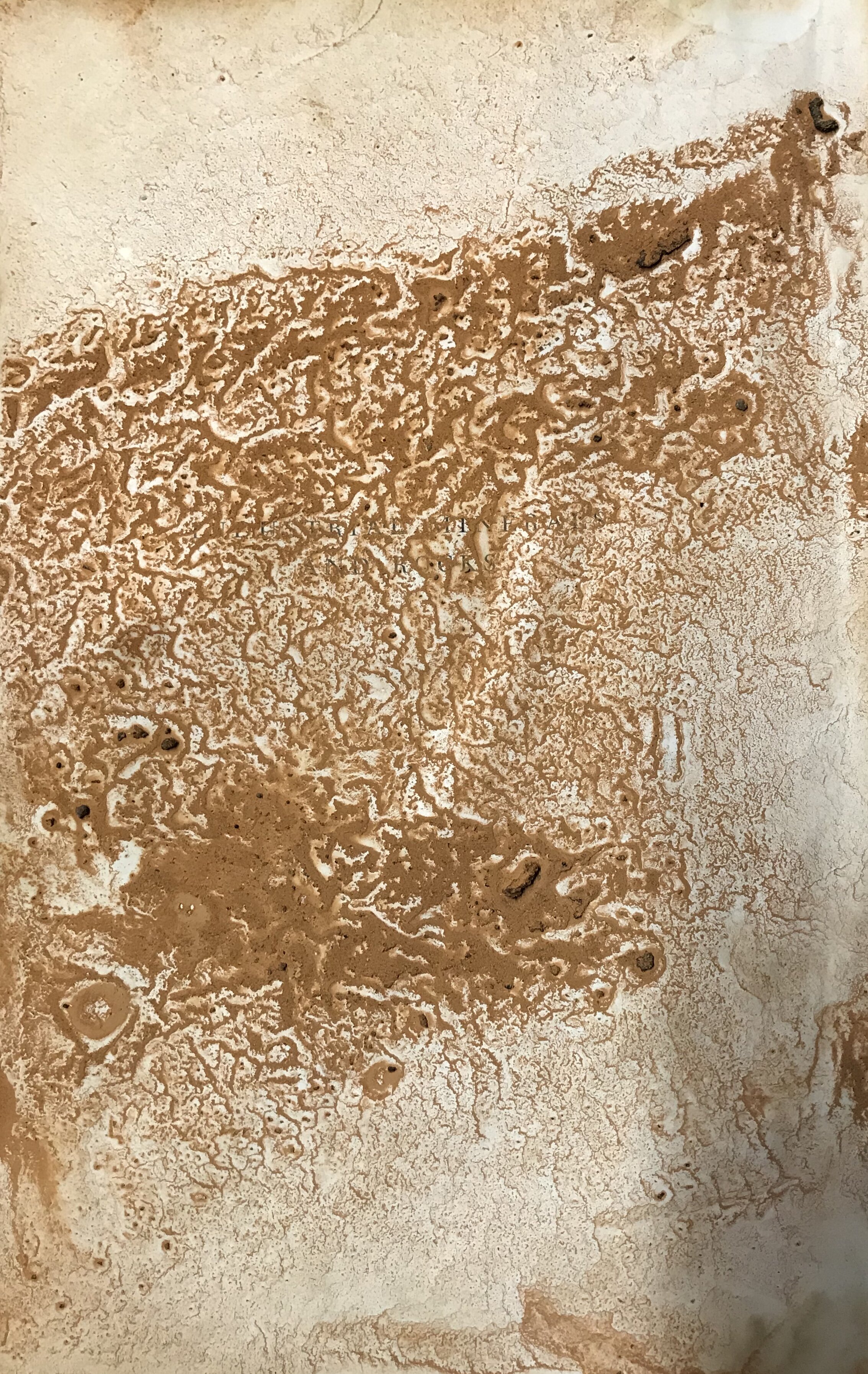

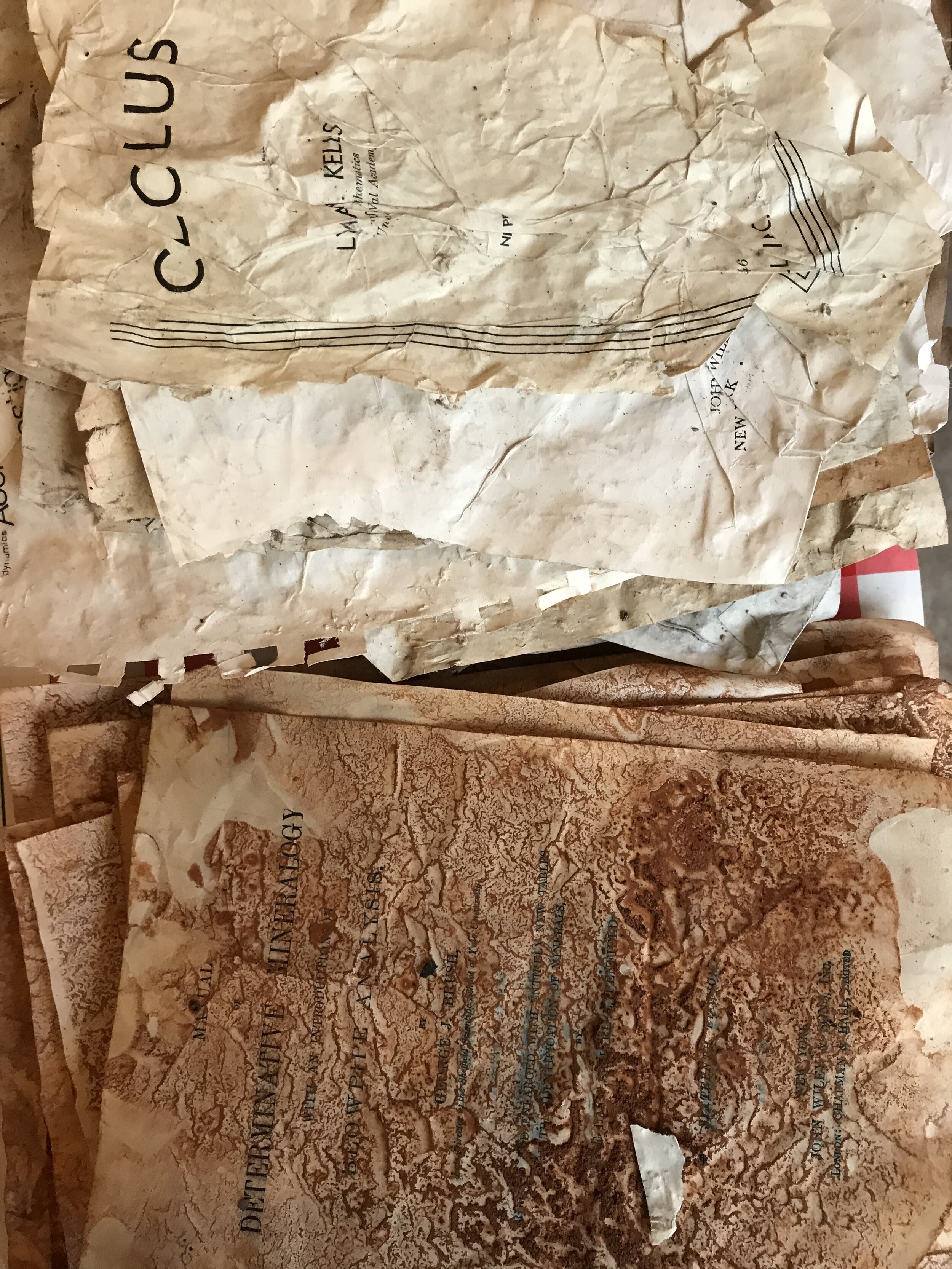

No words but textures to touch and feel. In preparation for this residency, I extracted pages from mining books. Here I found a place to use them by backing them with wheat paste and using the rock shapes from the wall to mold them. The stone wall shaped the pages and held the art.

Trying to keep warm in a cold place:

At Cill Rialaig, a prefamine village with 19th century ambiance, I was far from the world I knew without the distractions of the 21st century—internet, iPhone, daily news.

Instead I was preoccupied with keeping warm. No central heating, no insulation and cold stone walls & a slate ceiling. The turf eater (an Irish term for the wood stove) became my focus as it consumed the peat, the fuel used here. Discovering that peat was so fast burning, I found that the stove required vigilant attending to ensure uninterrupted warmth.

I went through many bags of peat and accumulated many pails of ash. So it became a material to experiment with in its various forms of brick, charcoal, ash and ink.